By Kasimir Rantzau.

Democracy entails the diversity of society – it provides the privilege for all that are eligible to vote. It is the foundation for a free society. However, electoral discrimination is also a reality of democracy. A resilient discriminating factor are the hurdles placed for non-English speakers to exercise their full right to vote.

How do our electoral proceedings attempt to make elections accessible to all non-English speakers? And how precisely do these provisions fall short in leveling voter accessibility?

Discrimination for non-English speakers is met on all aspects of the electoral process. In light of the Individual Electoral Registration, language proficiency has become ever more relevant. Language barriers pose immense difficulty for non-English speakers to register to vote.

Following, the election process itself also has barriers for non-English speakers. Our electoral system offers three forms of issuing one’s vote. At the polling station, through postal vote and in some cases through proxy vote. This is intended to provide valid opportunity for all that are eligible to vote. And yes, these three forms of delivering one’s vote do potentially cover all who wish to exercise their democratic right. However, the conditions, and thus ultimately the independence of one’s vote, is significantly different for people that face language disabilities towards conventional voting.

Being a non-English speaker, I am not automatically excluded to vote. Hypothetically, I can ask my English speaking cousin to translate my postal vote registration and the subsequent issuance of my vote. Through this help, I am able to issue my vote. If eligible I can also choose to issue my vote through a proxy. I ensure a person I trust with my vote. However, electoral scrutiny fails to uphold the confidentiality of my vote. In addition, through the nature of such proceedings, I am confined to the trust and support of a third person.

This has sparked debate and criticism. Even calls to ban the use of non-English or Welsh languages at polling stations arose in light to concerns that electoral scrutiny was reduced through the utilisation of interpreters. It is clear that a ban of non-English or Welsh languages at polling stations would further cause severe barriers for many to vote. However, concerns that interpreters could undermine elections by telling people how to vote is also an important issue that can, and must, be addressed through greater digitisation of electoral procedures.

Finally, to overcome my disability within the procedures that today’s electoral system provide is an immense inconveniency. A hurdle to be overcome, ultimately making it more difficult for me to practice my fundamental democratic right. In many ways creating severe discouragement to engage within our democracy.

The numbers

What are the numbers of non-English speakers. Who is affected through language discrimination? This can be looked at from two different angles. Based on language, the groups of non-English speakers can be identified. On the other hand, regionally.

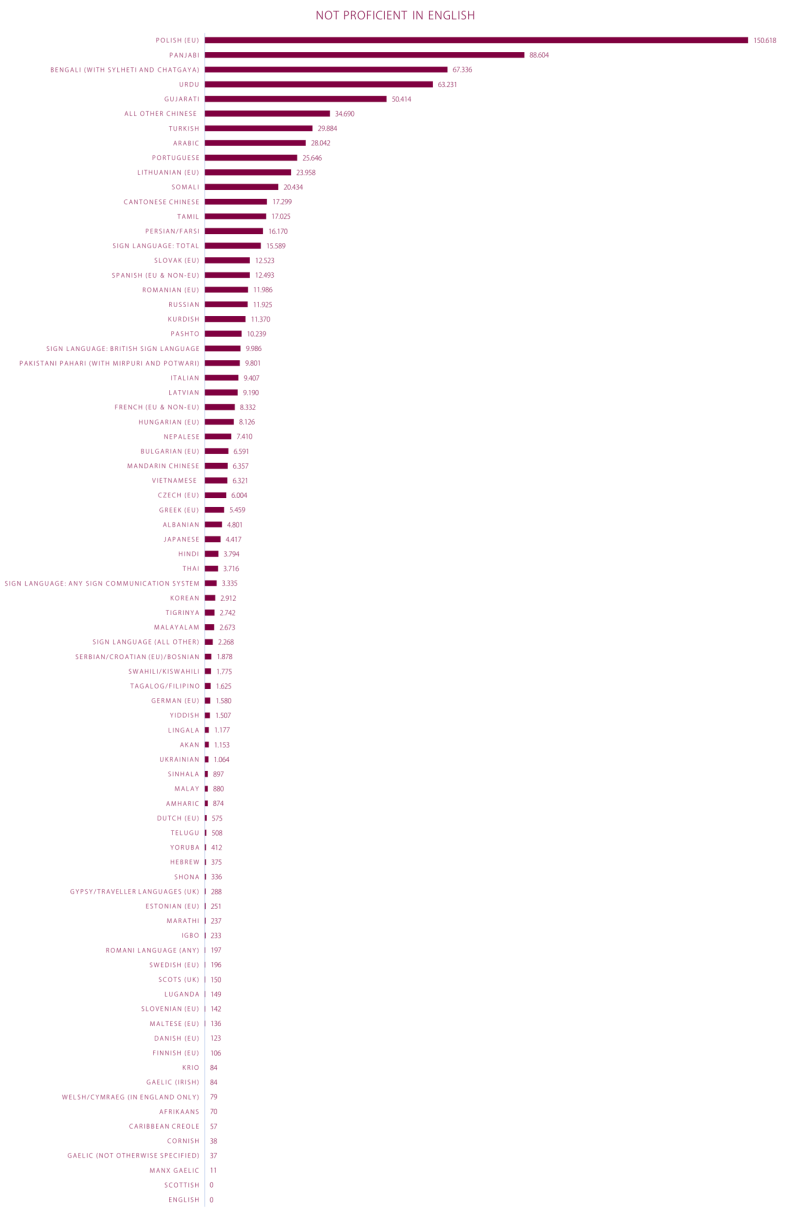

Table 1: Main language vs not proficient in English

863.150 people, cannot speak English or speak it well. Polish speakers lead the table followed by Panjabi and Bengali speakers. It is also vital to acknowledge that 15.589 people speak sign language. Of which 9.986 speak British Sign Language (BSL). Political manifestos and speeches have slowly become available in BSL reducing discrimination faced by people from the Sign Language community. However, voting still remains difficult. Members of the sign language community in many cases require help. The House of Commons: Political and Constitutional Reform Committee clearly outlines the shortcoming in preventing discrimination for BSL speakers. The remaining lack of information in BSL has caused accessibility issues to remain prevalent within electoral procedures (House of Commons, Political and Constitutional Reform Committee, 2014).

Regionally disparities can also be identified. England and Wales are filled with diversity. This becomes evident in the following diagrams; outlining in which parts of the country a reduction in language discrimination would be most urgent.

In the 2011 Census, collected data presents that language discrimination is likely to occur in urbanised areas of England and Wales. Newham (8,7%) leads the table when it comes to local authorities with the highest rate of non-English speakers. Brent and Tower Hamlets closely followed with each 8%. Boston and Leicester also have over 5% non-English speakers. Evident from the data, potential language discrimination is not only restricted to London, but throughout the country.

In effect, it can be feared that large amounts of people are either directly discriminated against, or are discouraged to take on the hurdles to register and issue their vote.

It can also be feared that ethnic groups are effectively discriminated against causing a lower representation for such groups. As acknowledged by the Electoral Commission, some Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) groups are significantly less likely to be registered to vote compared to those identifying as White British. (House of Commons, Political and Constitutional Reform Committee, 2014)

Table 2: Registered among those eligible (British and Commonwealth citizens)

| Ethnic Groups | Registered to vote at sample address | Said they were registered at another address | Not registered | N |

| Indian | 80 | 3 | 18 | 556 |

| Pakistani | 83 | 2 | 15 | 616 |

| Bangladeshi | 78 | 5 | 17 | 252 |

| Black Caribbean | 80 | 6 | 16 | 535 |

| Black African | 66 | 7 | 28 | 400 |

| Mixed white/black | 74 | 4 | 22 | 81 |

| All minorities | 78 | 4 | 19 | 2476 |

| White British | 91 | 2 | 7 | 2692 |

Source: BES 2010, EMBES 2010, weighted (Heath & Martin, 2013)

Anthony Heath and Jean Martin (2013) acknowledge minorities that face language barriers where far less likely to register to vote. When observing the data above, it becomes clear that minorities face far lower registration rates. It must, of course, be acknowledged that other factors also contribute to minorities having lower registration rates. However, one can make the case that general political apathy among minorities is only spiraled through language discrimination.

Digital – the solution?

Language discrimination is clearly a contributing factor for low voter registration among minority groups. This opens the discussion towards what are the failures in contemporary registration and voting procedures? The fact that in England and Wales registration is severely restricted towards non-English and in Wales non-Welsh speakers. Non-English speakers are reduced to receive assistance. Ultimately creating hurdles to issue one’s fundamental democratic right. Can a greater degree of digitisation provide the basis for all to register to vote? Arguably yes.

It can be suggested that voter accessibility would be greatly increased if voter registration and electoral procedure were accessible in the named languages that have high numbers of non-English speakers. With respect to resource allocation, electoral procedures should be digitally provided in the languages that the respective council or voter registration face most often. In other words, the urgency for electoral procedures being provided in Afrikaans is relatively low, considering its score in the 2011 Consensus. However, it is clear that, looking at table 1, that languages, such as Polish, Urdu, Bengali, British Sign Language, Panjabi, Arabic and Turkish have immense amounts of potential eligible voters discouraged from exercising their democratic right. The question that policy makers need to address is what languages to include. In addition, local areas can also specifically tailor their language requirements. Newham will have a greater urgency to provide voter accessibility in Bengali, whilst Ealing will perhaps rather require Polish.

One might however ask, to what degree digital voting, (in the respective languages utilised to reduce voter discrimination), will be effective? One can argue that certain demographic groups are will be less inclined to have and use technology which could enable them to vote. More specifically, age can be seen as a strong factor to determine if a group will be inclined to use technology to receive language assistance in electoral procedures.

Table 3 and 4: Age profiles by Male/Females

The data presented suggests that non-English speakers are most likely to be ranged into age 16-48, among both females and males. The second largest group that is likely to be non-proficient is between the age of 50-64. With regards to the wide availability of smartphone technology, we presume that a large majority of non-English speakers will have access to the technology required for digitalised electoral procedure. It is, however, important to find solutions to make this technology further available to prevent that older demographic groups remain excluded to electoral procedures.

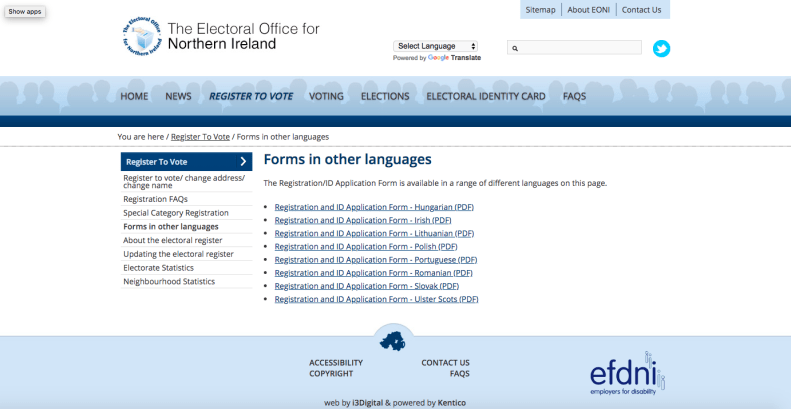

Northern Ireland has already taken positive action to integrate non-English speakers into electoral registration. The Electoral Office for Northern Ireland offers registration forms in eight additional languages. Including Irish, Polish and Romanian.

This is a positive step to overcoming voter discrimination, and defiantly puts to show the possibilities to overcome language barriers. The ultimate goal remains that voters are not discriminated in any process whilst exercising their democratic rights.

Kasimir Rantzau is a student in International Relations at the University of Westminster. This research will feed into WebRoots Democracy’s Cratos Project. Information about the Cratos Project can be found here.